Massage Methods and Physiological Mechanisms That May Help Ease Migraine Symptoms

Introduction and Outline: Why Massage Matters for Migraine Symptoms

Migraine is more than a tough headache; it is a neurological condition that can bring throbbing pain, nausea, sensitivity to light and sound, and a fog that blurs work, parenting, and daily routines. Globally, migraine is among the leading causes of years lived with disability in people under 50, and many individuals seek non-drug strategies to complement medical care. Massage appeals because touch can calm the nervous system, loosen rigid muscles, and create a breathing space during a stormy episode. At the same time, the evidence is mixed: small randomized trials and pragmatic studies suggest massage may reduce headache days, intensity, and medication use for some, but results vary and techniques differ. Safety and realism are key: massage is not a cure, but it may be a useful ally.

This article balances practical guidance with physiological context. You will find explanations of how touch affects pain signaling, circulation, and muscle tone, along with step-by-step ideas for self-care and pointers for finding a trained professional. The aim is to offer clear, respectful options without overpromising outcomes. If you have new, severe, or changing neurological symptoms, seek urgent medical evaluation before trying any manual therapy.

Outline of what follows:

– The migraine–massage connection: how mechanoreceptors, blood flow, and autonomic balance intersect with head pain

– Myofascial and trigger-point work for neck, jaw, and scalp tension that may feed into migraine symptoms

– Gentle pathways: craniosacral holds, lymphatic strokes, and scalp acupressure—what they aim to do and what the research shows

– A practical self-massage routine and scheduling ideas to support sleep and recovery

– Safety first: contraindications, red flags, and how to choose a practitioner who adapts techniques to your needs

From Nerves to Vessels: How Touch Might Modulate Migraine Biology

To understand why massage may help with migraine symptoms, it helps to sketch the physiology. A migraine attack involves activation and sensitization of the trigeminovascular system—nerves that innervate the meninges and blood vessels—leading to the release of inflammatory neuropeptides and a cascade of pain signaling. Central sensitization can follow, making ordinary touch feel irritating (allodynia). Many people with migraine also report neck stiffness or jaw clenching before, during, or after attacks. These musculoskeletal patterns can feed into sensitization, while stress and poor sleep can lower the threshold for the next episode.

Massage applies mechanical input to skin, fascia, and muscle that can influence these processes in several ways:

– Sensory gating: activating low-threshold mechanoreceptors (A-beta fibers) can inhibit nociceptive traffic in the dorsal horn, a “gate control” effect that may temporarily dim pain intensity.

– Descending inhibition: relaxing, rhythmic touch can engage brainstem circuits that release endogenous analgesic neurotransmitters, supporting top-down modulation of pain.

– Autonomic shift: slow, gentle strokes often increase parasympathetic tone and heart rate variability while easing sympathetic arousal; this calmer internal state can reduce triggers like muscle guarding and sleep disruption.

– Local circulation: kneading and stretching can improve microvascular flow and reduce myofascial adhesions, potentially easing pericranial tenderness that is common in migraine.

– Inflammation and stress chemistry: preliminary studies have linked massage with lower cortisol and perceived stress; while not specific to migraine, these changes can raise resilience.

Consider a practical example. Many individuals experience tenderness at the suboccipital muscles (the tiny stabilizers just under the skull). Gentle, sustained pressure here can soften hypertonic tissue, improve cervical mobility, and reduce referred pain along the temples. In small trials, multi-week series of neck and shoulder massage were associated with fewer headache days and better sleep quality, though sample sizes were modest and techniques varied. Importantly, intensity matters: applying deep, fast pressure during an acute, light-sensitive phase may backfire, while slower, lighter contact aimed at comfort and breath may be more tolerable.

Massage is unlikely to stop every attack, and not all mechanisms apply equally to every person. Yet when framed as a way to reduce allostatic load—lowering stress, smoothing muscle tone, and improving recovery—manual therapy can be a reasonable adjunct alongside preventive strategies, hydration, regular meals, and clinician-guided medications.

Myofascial and Trigger-Point Strategies for the Neck, Jaw, and Scalp

Many migraineurs notice that shoulder elevation, jaw clenching, and a stiff upper neck creep in around an attack. Myofascial techniques and trigger-point work aim to release taut bands, restore glide between layers, and reduce referred pain that often converges around the temples, forehead, or behind the eyes. Key regions include the upper trapezius and levator scapulae (shoulder girdle), sternocleidomastoid and scalenes (front and side of the neck), the suboccipitals (base of the skull), and the temporalis and masseter (jaw and temples).

Common techniques and how they differ:

– Myofascial release: slow, sustained pressure and stretch that tracks tissue resistance until it yields; useful for broad bands and fascial glide.

– Trigger-point compression: firm, tolerable pressure (aim for a 4/10 discomfort that eases) held 20–60 seconds on a distinct tender nodule, then released and rechecked.

– Cross-fiber friction: short strokes perpendicular to muscle fibers for adhesions near attachment sites, applied gently to avoid irritation.

– Stretch-and-breathe pairing: lengthening a region while guiding steady nasal breathing to downshift arousal.

Example sequence during a symptom-prone day: begin with heat on the upper shoulders for five to ten minutes to coax vasodilation, then apply gentle strokes from shoulder to skull to invite relaxation. Next, use two fingertips to sink slowly into the suboccipital area, holding until a softening is felt. Follow with light kneading of the temples and a palm sweep from forehead to hairline. Finish with jaw relaxation: place fingertips at the angles of the jaw, gliding forward toward the chin with minimal pressure while releasing the tongue from the roof of the mouth.

Evidence suggests that multi-week programs combining neck and shoulder massage with home practice can reduce headache intensity and frequency in some people, particularly when tension-type features overlap with migraine. However, dosage matters: two to three sessions per week for four to six weeks, plus brief daily self-care, appears more effective than sporadic visits. Safety notes include avoiding aggressive pressure on the front of the neck, wary work over the carotid sinus, and caution with conditions such as recent whiplash, clotting disorders, or severe osteoporosis.

Self-care options that require no equipment include a tennis ball against a wall to address upper trapezius trigger points, gentle chin nods for the suboccipitals, and slow nasal breathing to pair with each stroke. The guiding principle is “comfortably challenging,” never forcing tissue that guards or increases throbbing.

Gentle Pathways: Craniosacral Holds, Lymphatic Flow, and Scalp Acupressure

Some approaches emphasize feather-light contact, aiming to calm the nervous system and facilitate fluid movement. Craniosacral-style holds use still, soft hand placements at the base of the skull, along the cranial sutures, and on the sacrum. Advocates suggest these techniques downshift sympathetic tone and ease dural tension. Evidence is evolving and mixed—some small studies and case series report symptom reduction and improved quality of life, while others call for stronger trials. A practical takeaway is to treat these methods as relaxation-forward options that can complement more targeted myofascial work.

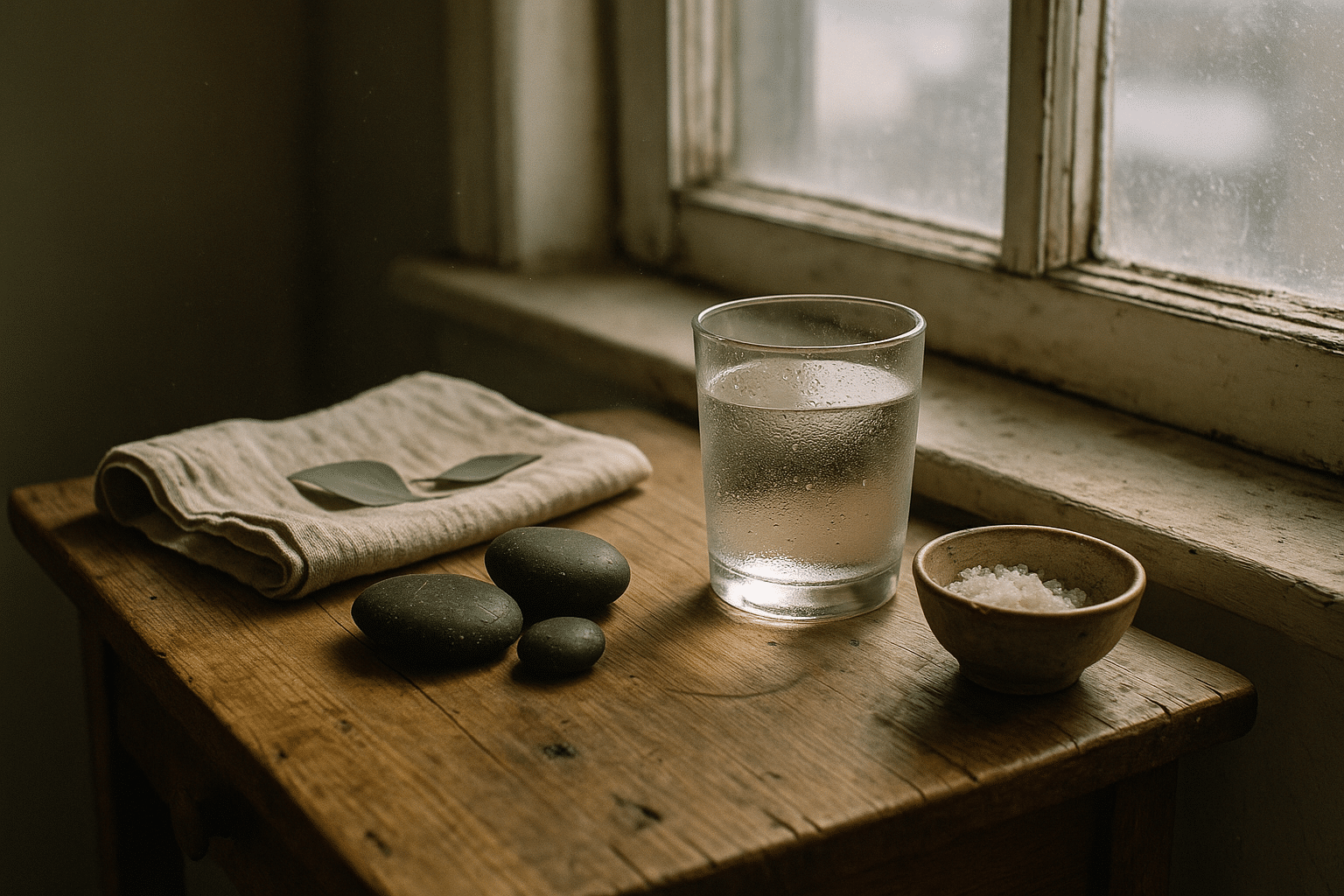

Lymphatic-focused strokes use gentle, directional sweeps to encourage fluid clearance from the face and scalp toward the neck. When congestion, facial pressure, or a “puffy” sensation amplify migraine discomfort, these motions can feel soothing. A typical sequence might start at the supraclavicular fossae (the soft notches above the collarbones), then outline the jawline from chin to ear, sweep from cheekbones toward the ears, and finish with light strokes from the temples toward the hairline and down behind the ears. Pressure is minimal—think the weight of a coin—because lymphatic channels respond to skin-level stretch rather than deep kneading.

Scalp acupressure offers another accessible pathway. Without relying on needles, you can target pericranial tenderness and common referral zones using steady finger contact. Locations often reported as helpful include the hollows just under the skull on either side of the spine, the soft tissue at the base of the temples, the ridge above the ear where the temporalis meets the scalp, and the web between the thumb and index finger or between the big toe and second toe. Hold each point for one to two slow breaths, inviting a wave of relaxation before moving on.

How do these gentle methods plausibly work?

– Autonomic regulation: the slow pace and light force may increase vagal activity, easing nausea and restlessness that accompany migraine.

– Reduced pericranial tenderness: soft contact can decrease guarding and improve tolerance to touch (important when allodynia is present).

– Sleep support: many people report easier sleep after sessions, and better sleep itself can raise the threshold for attacks.

– Low risk profile: when performed with care, these approaches generally have few adverse effects, though individuals with active skin infection, recent surgery, or acute neurological deficits should defer and consult clinicians.

Comparatively, these techniques favor subtlety over intensity. They may not resolve deep trigger points, but they excel at lowering arousal and easing the sensory “volume knob.” Pairing them with brief, precise myofascial interventions often yields a balanced session that soothes without overstimulation.

Putting It All Together: A Safe, Realistic Routine and When to Seek Help

Think of massage for migraine symptoms as a toolkit you can scale to the day. On a quieter day between attacks, you might devote 20–30 minutes to neck and scalp work to address stiffness and keep thresholds higher. During an oncoming wave, five to ten minutes of very gentle, breath-synced touch may be all that feels tolerable—and that is fine. Consistency, pacing, and self-observation matter more than any single “perfect” stroke.

Sample 20-minute self-care session:

– Minute 0–3: focus on slow nasal breathing; lightly place a hand on the chest and one on the belly to lengthen the exhale.

– Minute 3–7: apply soft strokes from shoulders to base of skull, staying within comfort; add small circles at the upper trapezius.

– Minute 7–10: sustained fingertip hold at the suboccipitals; release when a softening arrives.

– Minute 10–14: gentle temple and forehead sweeps toward the hairline, then down behind the ears to encourage fluid flow.

– Minute 14–18: jaw relaxation glides from back to front; avoid clenching by letting the tongue rest low.

– Minute 18–20: sit quietly, notice changes in breath and light sensitivity, and hydrate.

Scheduling ideas and expectations:

– Begin with three short sessions per week, then adjust based on response.

– If working with a professional, consider a series of weekly appointments for four to six weeks, combined with brief daily self-care.

– Track outcomes that matter to you: headache days, intensity, medication use, sleep quality, and ability to function.

Safety and red flags—pause massage and seek medical advice if any appear:

– Sudden, severe headache described as “worst ever,” new neurological deficits, confusion, or weakness.

– Headache after head or neck injury, or with fever and stiff neck.

– Unexplained visual changes, chest pain, or shortness of breath.

– Known clotting disorders, active skin infections, or recent surgery in the area being treated.

Choosing a practitioner:

– Look for licensing or registration where you live, plus additional training in headache, neck, and jaw care.

– Ask how they adapt pressure during light-sensitive episodes, and whether they provide home strategies.

– Expect a collaborative plan that respects medications and other therapies recommended by your clinician.

Conclusion: Massage can support people living with migraine by easing pericranial tenderness, calming the nervous system, and nurturing sleep. Results vary, and the aim is steady, sustainable relief rather than dramatic one-session changes. Paired with medical guidance, hydration, movement, and regular meals, these touch-based methods offer a grounded, practical way to nudge the brain–body system toward calmer days.