How Enzymatic Cleaners Break Down Organic Molecules to Neutralize Pet Odors at the Source

Roadmap and Why Odor Neutralization Starts with Chemistry

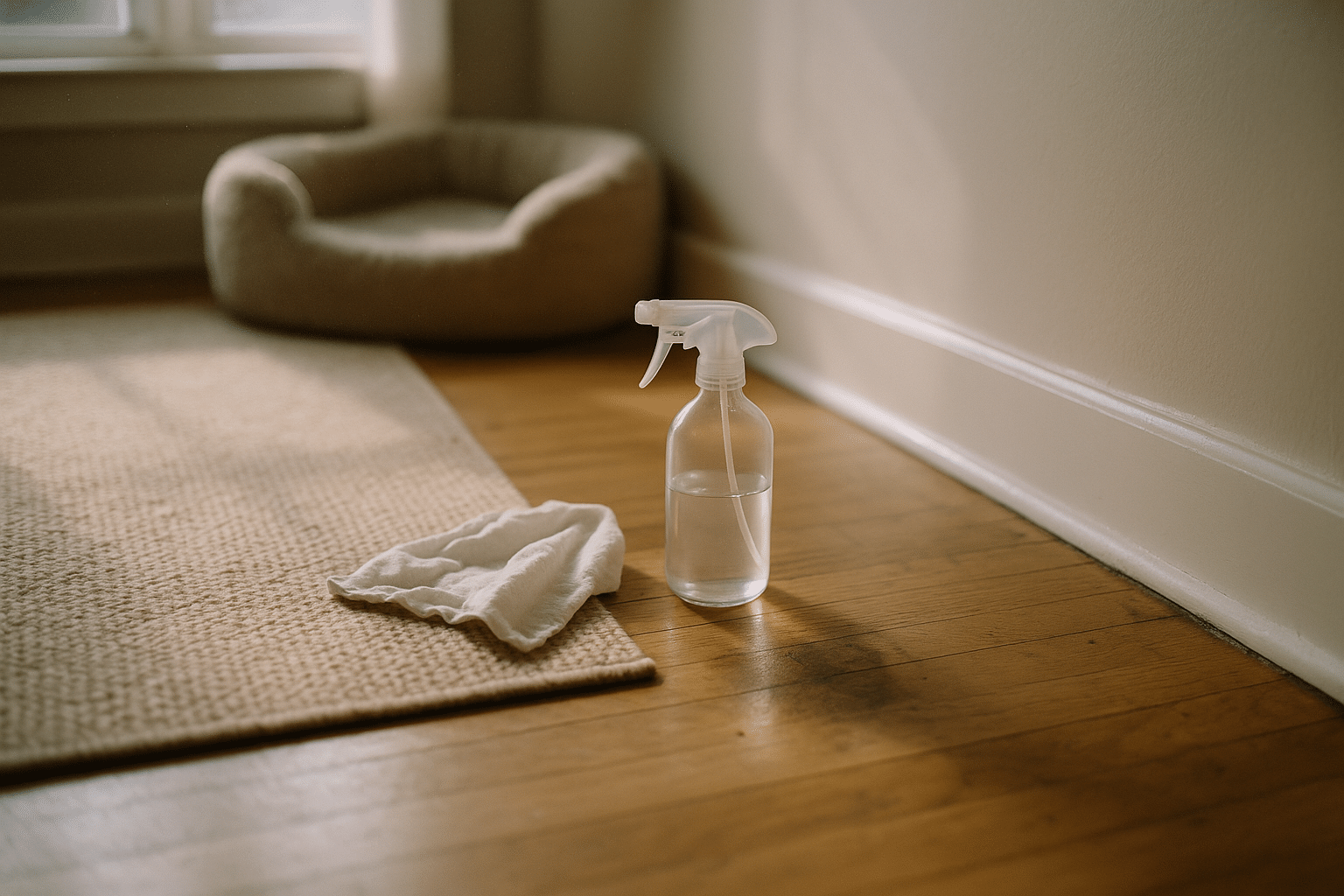

Pet odors are a chemistry problem first and a cleaning problem second. What we smell is a cocktail of volatile molecules released from residues like urine, vomit, feces, saliva, and skin oils. These residues soak into porous materials—carpet fiber, padding, grout, unfinished wood, even concrete—and then slowly off-gas over days or weeks. Quick fixes that mask scent often fade because the source compounds remain intact. Enzymatic cleaners approach the task differently by targeting the actual molecular bonds holding those odor-causing residues together. Think of them as tiny, specialized scissors: each enzyme type snips one class of molecule into smaller, non-odorous fragments that can be blotted or rinsed away.

Before we dive deeper, here’s the outline for what follows:

– The science of pet odors: what’s in urine and organic spills, and why smells persist.

– How enzyme systems (proteases, lipases, amylases, and urease) dismantle specific molecules.

– Enzymatic cleaners compared with oxidizers, disinfectants, and fragrances.

– Application science: coverage, dwell time, moisture, pH, and surface types.

– Conclusion with actionable steps for consistent, safe, and durable odor control.

Why this matters: pet urine, for example, starts near neutral to slightly acidic (often around pH 6), dominated by urea, salts, creatinine, and, in cats especially, concentrated uric compounds. As time passes, microbes and environmental factors convert urea into ammonia, raising pH and intensifying odor. Uric acid can form crystals and insoluble salts that lock into carpet backing or porous subfloors. Without breaking these structures apart, you can scrub, spray, and still catch a whiff days later. Enzymatic cleaners are engineered to operate under typical household conditions—room temperatures and near-neutral pH—so they catalyze the breakdown of proteins, fats, starches, and urea that fuel these lingering smells. The result is a more thorough path toward true neutralization rather than temporary concealment.

The Science of Pet Odors at the Molecular Level

Understanding odor at its source makes every cleaning decision easier. Fresh urine is largely water plus urea, electrolytes, small amounts of proteins and amino acids, and species-specific metabolites. In cats, urine is often more concentrated than in many other household animals, which is one reason small accidents can produce outsized scent. Over time, urease-positive microbes and environmental conditions hydrolyze urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. Ammonia is pungent and alkaline, which both magnifies the smell and can shift the environment in a way that changes how fibers and residues behave. Meanwhile, uric acid—poorly soluble in water—can crystallize into urate salts that cling to substrates. These crystals are tenacious, resisting casual rinsing and reactivating with humidity.

Organic stains also include an array of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates. Proteins can break down into amines and sulfur-containing compounds (like thiols), both of which are notorious for strong smells. Lipids oxidize, forming volatile fatty acids and aldehydes that contribute to rancid or sour notes. Carbohydrates, while not always smelly by themselves, feed resident microbes; microbial metabolism can then generate additional volatiles. When these compounds absorb into capillaries within carpet backing or wick into porous grout and concrete, the surface may look clean while deeper reservoirs continue to emit odor. That’s why a spill can seem to “return” after drying or after a humid day—it never truly left.

Another layer is pH. Many enzymes operate most efficiently near neutral pH (roughly 6–8), and the odor landscape shifts as pH changes. Aging urine trending alkaline (due to ammonia formation) can damage certain dyes or finishes and can also promote the persistence of urate deposits. Temperature and moisture matter, too: warmth improves diffusion and enzyme kinetics up to a point, and adequate moisture is needed for both enzymes and microbial helpers in bio-enzymatic formulations to function. Conversely, extreme heat can denature enzymes, while overly dry conditions stall reactions. These intertwined variables explain both why some odors are so persistent and why a methodical, chemistry-aware approach pays off.

How Enzymatic Cleaners Work: Mechanisms, Conditions, and Real-World Scenarios

Enzymes are biological catalysts that accelerate reactions without being consumed, often explained by the “lock-and-key” and “induced-fit” models. Each enzyme recognizes a particular substrate and reduces the activation energy required to cleave a specific bond. In enzymatic cleaners, several enzyme classes often work together:

– Proteases: cleave peptide bonds in proteins, reducing them to small peptides and amino acids that are less odorous and easier to rinse.

– Lipases: cut ester bonds in fats and oils, turning triglycerides into glycerol and fatty acids that are less sticky and less smelly.

– Amylases: break down starches and complex carbohydrates, eliminating food residues that feed odor-causing microbes.

– Urease: hydrolyzes urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide; in well-formulated systems, subsequent steps and rinsing remove or neutralize the ammonia.

Some products are “bio-enzymatic,” combining enzymes with beneficial bacteria that continue producing enzymes over time when moisture and nutrients persist. The idea is a tag-team effect: enzymes start the dismantling immediately, while microbes extend cleaning into micro-pores and fibers. Successful use hinges on conditions. Most household enzyme blends are optimized for room temperatures (roughly 15–40°C/59–104°F) and near-neutral pH. Too high a temperature (like from steam) can denature enzymes, and strong alkaline or acidic cleaners used beforehand can damage their activity. That’s why directions often advise against mixing chemistries or following with bleach or quaternary disinfectants.

Coverage and dwell time are crucial. Odors often extend beyond the visible stain via wicking, so saturating slightly past the perimeter helps reach hidden residues. For carpet over padding, the source is frequently in the pad or even the subfloor. A practical example: a cat urine spot that looks quarter-sized on top can be palm-sized in the pad. Saturating down to the pad, maintaining contact for 30–60 minutes for fresh accidents and several hours (even overnight under plastic to prevent drying) for set-in odors, and allowing a slow air dry can markedly improve outcomes. Repeat cycles may be necessary for heavy deposits or older stains. The overarching mechanism is consistent: catalyze the breakdown, keep the contact sufficient for the chemistry to finish, and remove the byproducts through blotting and ventilation.

Enzymatic vs Other Approaches: What Works Where and Why

Not all cleaners solve the same problem, and comparing approaches helps you choose wisely for each surface and situation. Enzymatic cleaners excel at organic, pet-related soils because they target specific bonds and work within everyday home conditions. By contrast, oxidizers—including solutions based on oxygen-releasing compounds—chemically alter or decolorize residues via oxidation. This can be effective for stain appearance and some odor contributors, but on certain dyes or natural fibers it can cause lightening, and oxidation alone may not fully disassemble urate crystals embedded in pores. Chlorine-based oxidizers are powerful but can discolor fabrics, corrode metals, and leave a residual scent that some users find harsh.

Quaternary ammonium disinfectants are designed primarily to reduce microbial load. They can assist with freshness by suppressing microbial metabolism that generates odors, but without removing the underlying organic mass, smells may return as residues persist or as remaining microbes recolonize. Fragrance sprays simply overlay the odor profile with new scent notes; they have a place for short-term comfort, yet they do not address the source.

Surface-by-surface considerations matter:

– Carpets and rugs: enzymatic systems are often a strong choice; adequate saturation to reach padding is key. Exercise caution with wool or silk, as proteases can affect protein-based fibers; spot-test in an inconspicuous area.

– Upholstery: similar to carpet, but watch for colorfastness and limited saturation to avoid watermarking. Gentle, repeated applications tend to outperform aggressive scrubbing.

– Hardwood: finished, sealed wood is more forgiving; promptly wipe excess moisture. Unfinished or lightly finished wood may absorb deeply—multiple light applications and rapid dry times reduce warping risk.

– Tile and grout: grout is porous; allow extended dwell time and ensure thorough rinse to remove byproducts from pores.

– Concrete and masonry: highly absorbent; multiple wetting cycles with extended contact, followed by good ventilation, are often needed.

Safety and indoor air quality also factor into the choice. Enzymatic formulas are typically water-based and operate at moderate pH, which supports a low-residue, low-fume workflow when used as directed. They can be incompatible with hot water extraction immediately after application; high heat risks enzyme inactivation. Rather than chasing a universal solution, match the chemistry to the job: use enzymes for organic odor sources, consider oxidizers cautiously for discoloration or non-organic soils, and reserve disinfectants for hygiene goals unrelated to odor bonds. This approach respects both the material you’re cleaning and the chemistry responsible for the smell.

Conclusion and Actionable Next Steps

Bringing it all together, enzymatic cleaners succeed because they break apart the complex molecules that make pet odors stubborn—proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and urea—turning them into smaller, less volatile fragments that you can rinse or blot away. They do their best work under common household conditions, with adequate moisture, time, and coverage. The biggest shift is adopting a source-focused mindset: instead of chasing scent at the surface, deliver the treatment where the residue actually lives and give the chemistry enough time to finish.

Here’s a practical playbook you can adapt to most pet-related odor situations:

– Act quickly on fresh accidents: blot, don’t rub; remove as much liquid as possible before chemistry.

– Saturate past the visible edge: reach carpet padding or grout pores by slightly oversizing the treatment zone.

– Allow generous dwell time: 30–60 minutes for fresh spots; several hours or overnight (kept moist under plastic) for set-in odors.

– Maintain favorable conditions: room temperature, avoid mixing with strong acids/alkalis or disinfectants before the enzyme step, and skip steam heat that can denature enzymes.

– Dry thoroughly and ventilate: after the reaction, blot, rinse lightly if appropriate, and let the area dry fully; repeat cycles for heavy deposits.

– Use care with sensitive materials: spot-test wool, silk, and delicate finishes; on porous stone like marble or limestone, avoid acidic products that could etch.

– For deep subfloor contamination: after enzymatic treatment and drying, sealing the subfloor may be necessary to lock in residual odors.

If recurring smells persist despite careful application, consider whether the contamination sits deeper than expected or spans a larger area due to wicking. In multi-layer structures (carpet-pad-subfloor), success sometimes comes from methodical, repeated low-aggression cycles rather than one heavy application. For dense, old odors in concrete or unfinished wood, a series of treatments over days can outperform a single marathon session.

For pet guardians and home caretakers, the takeaway is straightforward: let biology help you. Choose an enzyme formula suited to organic soils, apply it where the odor truly resides, protect the contact time, and be patient with porous materials. This steady approach delivers cleaner surfaces and calmer noses without relying on harsh fumes or perpetual perfume. With a bit of chemistry on your side, the space you share with your animals can smell as welcoming as it feels.